New Article: Maps of a Nation

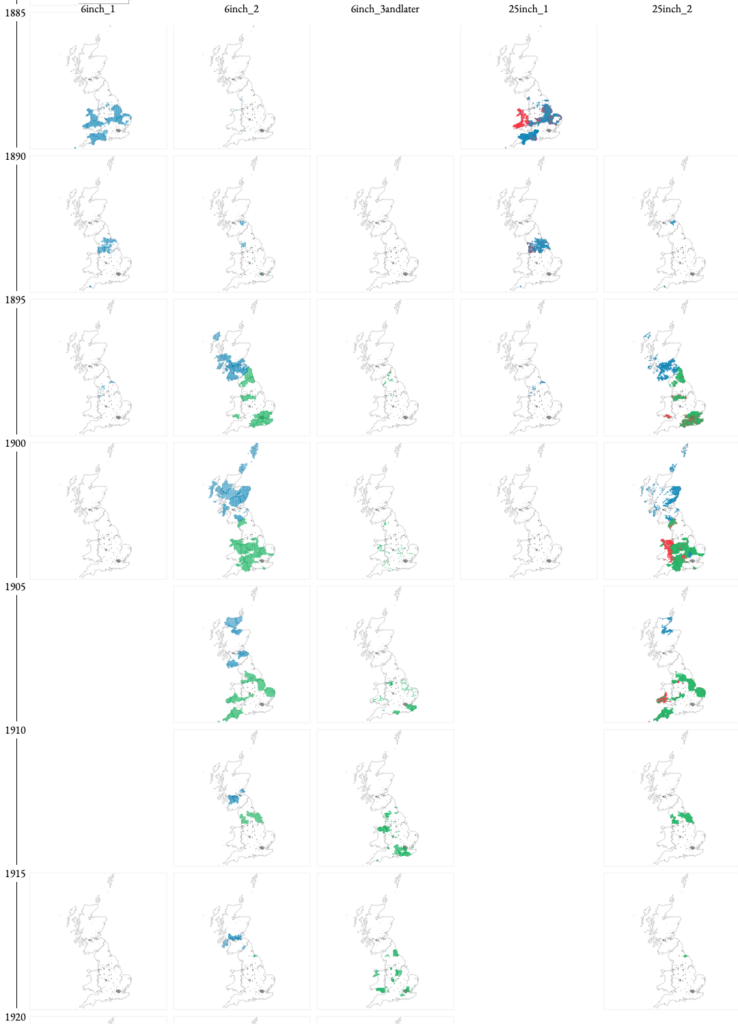

We have published a new Open Access article in the Journal of Victorian Culture about using Computer Vision with historical maps. ‘Maps of a Nation?’ describes our Computer Vision pipeline for working with thousands of maps at once, which enables new forms of historical inquiry based on spatial analysis.

The Ordnance Survey has been the subject of great research (for example, Map of a Nation by Rachel Hewitt – the book that inspired our title). But historians have not used entire editions of OS series as primary sources. You can browse the 6-inch-to-the-mile 2nd Edition OS maps, for example, on the NLS portal (after filtering for dates before 1914). This piecemeal approach to OS maps has evolved partly for disciplinary reasons & partly for the technical reason that high-quality maps have not until recently been available digitally, geo-referenced, and in colour.

Furthermore, access to item-level metadata is a prerequisite for a collection to become a searchable corpus for humanities research. Unfortunately, very few collections have this level of detailed metadata. This is a major ‘AI for LAM’ challenge: it’s an area where historians, data scientists, & curators can collaborate. With metadata we not only get a sense of the complex temporality of these maps (editions aren’t simple snapshots in time) but also a valuable view onto what’s available for analysis: what sheets did the OS make? (when & where) + what’s been digitised? (Lots! But not all.)

Researchers in Geography and GIScience as well as Economic History are testing these waters by extracting certain map content automatically, because the challenges of building this data by hand are prohibitive (above all the significant investment of time). We set out to ask: what would a CV pipeline for working with maps look like if it was designed from the outset with humanities research in mind? How do we honour the visual continuity of map content, rather than treating it as something to be mined for discrete pieces of information? And how do we build a method that is malleable enough not only to allow for, but to encourage, changes in what researchers want to find on a map?

As an image classification task created specifically for flexible, humanistic investigation of the high-resolution contents of historical maps, our ‘Patchwork method’ draws on the longstanding desire to adopt a ‘complete’ view of a territory. We highlight parallels between the situation faced by today’s users of digitised maps, and a similar inflexion point faced by their predecessors in the 19th century, as the project to map the nation approached a form of completion.

So many Living with Machines colleagues have helped this work along. Thanks team!!

Finally, we would be nowhere without Chris Fleet and the National Library of Scotland (check out the NLS map collections online). Even as digitised maps become more widely available as sources for historical research, working with them at scale remains a serious challenge. The new forms of research we have outlined in this project are only possible thanks to the enormous efforts of staff at the NLS.